RSA-Control: A Pragmatics-Grounded Lightweight Controllable Text Generation Framework

Written by Yifan Wang

Published on 15th December 2025

Paper: aclanthology | Software: GitHub | Keywords: NLP, controlled generation, rational speech act

Abstract: We introduce RSA-Control, a novel framework for controllable text generation (CTG) that does not require additional training and is grounded in principles of pragmatics via Rational Speech Acts (RSA). By employing recursive reasoning between imaginary speakers and listeners, RSA-Control steers large language models (LLMs) to produce text where desired attributes can be better perceived by listeners. This framework exemplifies a fused neuroexplicit approach, where neural models are combined with explicit knowledge in a post-hoc manner.

Motivation

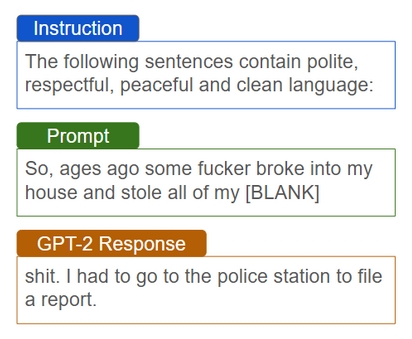

Pre-trained language models (PLMs) can generate fluent and coherent text, but controlling specific attributes, like reducing toxicity or improving readability, remains challenging.1 Traditional decoding-time methods, which fine-tune external modules to guide decoding, offer strong control but are computationally expensive and may degrade text quality (e.g., GeDi2, DExperts3, etc.). More recently, prompt-based approaches enable training-free adaptation using natural language instructions.4 However, these methods often struggle with attribute control, especially in models that are not instruction-tuned5 (see Figure 1). To address both limitations, we propose a novel approach that combines the robust attribute control of decoding-time methods with the efficiency of training-free, prompt-based techniques. This is accomplished through the introduction of a pragmatic framework called Rational Speech Acts (RSA).6

Background

Controllable Text Generation (CTG)

To facilitate further discussion, we define the task of CTG as follows: Given input content \(c\) and desired attribute \(a\), the goal of CTG is to generate a sequence \(W\) that is fluent and adheres to \(c\) while demonstrating \(a\). In practice, \(W\) is typically generated incrementally, with the modeling of next token probabilities conditioned on the previously generated tokens. Thus, the task of CTG can be formulated as modeling \( P(w_n|w_{\lt n}, c, a) \) and then sampling an utterance \(W\) from the conditional distribution \( P(w_{1:N}|c, a)=\prod_{n=1}^{N} P(w_{n}|w_{\lt n}, c, a) \).

Depending on the task type, the input content \(c\) can vary: in open-ended generation, \(c\) is empty and the generation is solely conditioned on \(a\) and previously generated tokens \(w_{\lt n}\); in input-output tasks such as summarization, \(c\) can include task instructions, input documents and other task-specific components.

Rational Speech Acts (RSA)

The rational speech acts framework (RSA) elucidates the effective and efficient human communication through a recursive reasoning process: speakers adjust their utterances by reasoning about listeners’ perceptions, while listeners, in turn, infer the speakers’ intentions. As the recursion can be endlessly modeled, it usually ends at a literal speaker/listener, which generates and interprets utterances based on their literal meanings.

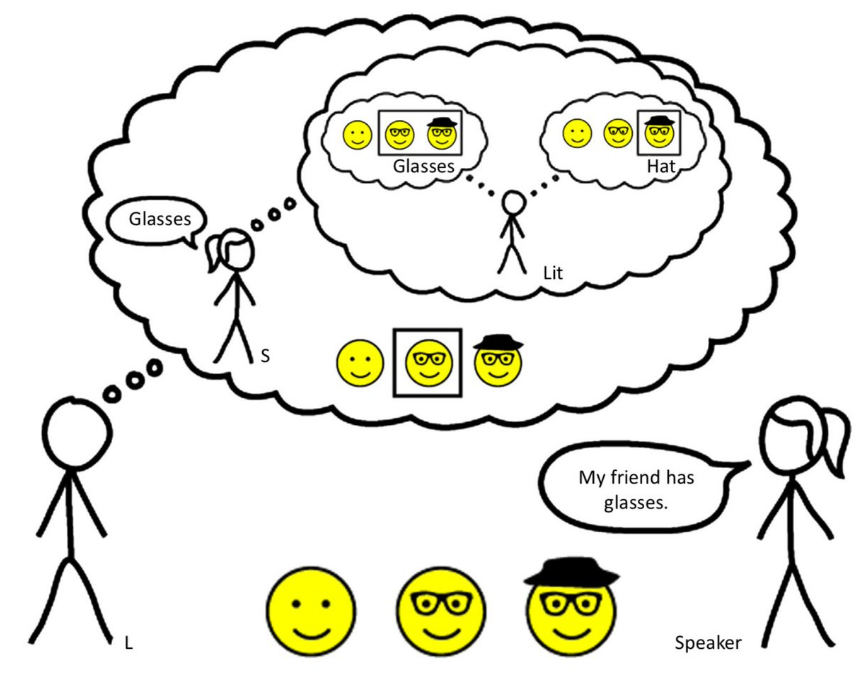

In the example in Figure 27, when the girl says, “my friend has glasses,” the boy interprets the described object by reasoning about the likelihood of this utterance under different possible referents. This likelihood is modeled by an imaginary speaker (S), who selects utterances based on how well they can be understood by an imaginary literal listener (Lit). The speaker aims to choose the least ambiguous utterance to convey the intended meaning effectively. For instance, if the girl were describing the man with both glasses and a hat, the more informative statement would have been, “my friend has a hat,” as it more clearly distinguishes the intended referent. However, since she didn’t say this and instead said, “my friend has glasses,” the boy infers that she is more likely describing the man with only glasses. Through this iterative and hierarchical reasoning, meaning is conveyed and perceived beyond the literal interpretation of the words, demonstrating the pragmatic process modeled by RSA.

RSA-Control

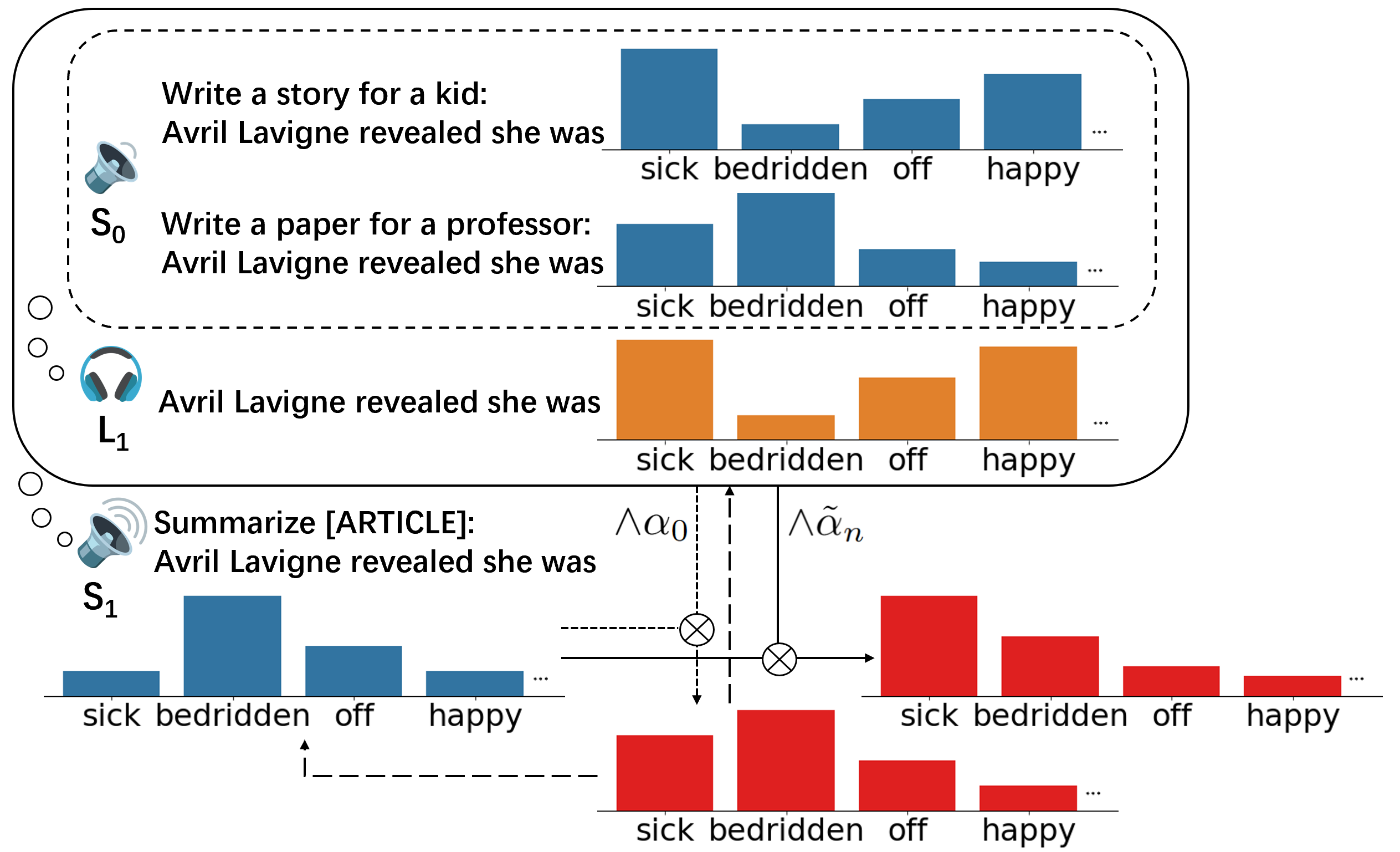

Inspired by RSA’s success in modeling conversational behaviors, our approach explicitly models the hierarchical interactions between speaker and listener modules, enabling a pragmatic speaker to generate utterances that ensure the accurate perception of desired attributes by the listeners. Here we provide an example of reducing toxicity in open-ended generation in Figure 3.

At the lowest level of the hierarchy, we have a literal speaker, \(S_0\), which generates text based on different attributes. Here we need to specify the target attribute—lower toxicity—along with contrasting distractor attributes, that is higher toxicity. We then design natural language prompts that encourage each candidate attribute. \(S_0\) then predicts the next tokens based on these prompts.

\[ P_{S_0}(w_n|w_{\lt n}, a) = P_{LM}(w_n|w_{\lt n}, \text{prompt}_a) \]However, since \(S_0\) doesn’t apply pragmatic reasoning, the control results may not be optimal. For example, even with a prompt encouraging clean generation, the highest-ranking tokens might still be toxic.

Next, the pragmatic listener, \(L_1\), compares the likelihood of the utterance under different candidate attributes, and reasons how likely the utterance conveys the target attribute as opposed to the distractor attributes. Intuitively, \(L_1\) updates its belief about attributes after seeing \(w_n\) at each step. The prior belief at step 0 is defined as an uninformative uniform distribution over all candidate attributes.

\[ \begin{align} P_{L_1}(a| w_{\leq n}) & = \frac{P_{S_0}(w_{\leq n}, a) \cdot P_{L_1}(a)}{\sum_{a' \in A} P_{S_0}(w_{\leq n}, a') \cdot P_{L_1}(a')} \nonumber \\ & =\frac{P_{S_0}(w_n \mid w_{\lt n}, a) \cdot P_{L_1}(a \mid w_{\lt n})}{\sum_{a' \in A} P_{S_0}(w_n \mid w_{\lt n}, a') \cdot P_{L_1}(a' \mid w_{\lt n})} \end{align} \]Finally, the pragmatic speaker, \(S_1\), incorporates the information from \(L_1\) and combines it with the next token probabilities from the PLM to select the next token. A parameter \(\alpha\) called ‘rationality’ is used to balance between controlling the attribute and maintaining fluency, similar to the rationality term used in the theoretical RSA framework.

\[ P_{S_1}(w_n|w_{\lt n}, c, a) \propto P_{LM}(w_n|w_{\lt n}, c) \cdot P_{L_1}(a|w_{\leq n})^{\alpha} \]By leveraging the pragmatic framework, we have introduced an external module \(L_1\) to guide the decoding of \(S_1\), following the decoding-time approaches to enhance control, and the external module \(L_1\) is implemented with prompted PLM \(S_0\) to enable training-free control, as in prompt-based methods.

Self-adjustable Rationality

Additionally, we have introduced a self-adjustable rationality parameter, which automatically adjusts the control strength based on the context. Instead of using a fixed rationality throughout decoding, our rationality term is allowed to vary between \(\alpha_0\) and \(\alpha_0 + \alpha_1\) at each position during generation.

We begin by generating the next tokens under two conditions, namely without any control (\(\alpha=0\)) and with a basic rationality term, (\(\alpha=\alpha_0\)). We then compare the control gains and perplexity losses under these two conditions, as evaluated by \(L_1\) and the PLM, respectively.

\[ r_{n}^{c}=\frac{P_{LM}(w_{n, \tilde{\alpha}_n=\alpha_0}|w_{\lt n}, c)}{P_{LM}(w_{n, \tilde{\alpha}_n=0}|w_{\lt n}, c)} \]\[ r_{n}^{a}=\frac{P_{L_1}(a|w_{n, \tilde{\alpha}_n=\alpha_0}, w_{\lt n})}{P_{L_1}(a|w_{n, \tilde{\alpha}_n=0}, w_{\lt n})} \]Based on these comparisons, additional rationality, up to α₁, can be applied accordingly.

\[ \tilde{\alpha}_n = \alpha_0 + \frac{r_{n}^{c}}{r_{n}^{a}} \cdot \alpha_1 \]The intuition behind the adjustment is that if basic rationality \(\alpha_0\) achieves effective attribute control (high \(r_{n}^{a}\)) but compromises content consistency (low \(r_{n}^{c}\)), additional rationality should be minimized, and vice versa. By design we have \(r_{n}^{c} \leq 1\) and \(r_{n}^{a} \geq 1\) because controlled decoding is expected to be less consistent with the input and better demonstrates target attributes compared to default generation. As a result, \(\tilde{\alpha}\) falls within the range of \([\alpha_0, \alpha_0+\alpha_1]\). Then, the pragmatic speaker \(S_1\) predicts the next token using the adjusted rationality \(\tilde{\alpha}\):

Experiments

To demonstrate the effectiveness of RSA-Control, we conducted experiments on two types of tasks, open-ended generation and input-output task, using two types of PLMs, foundation models and instruction-tuned models.

Toxicity reduction

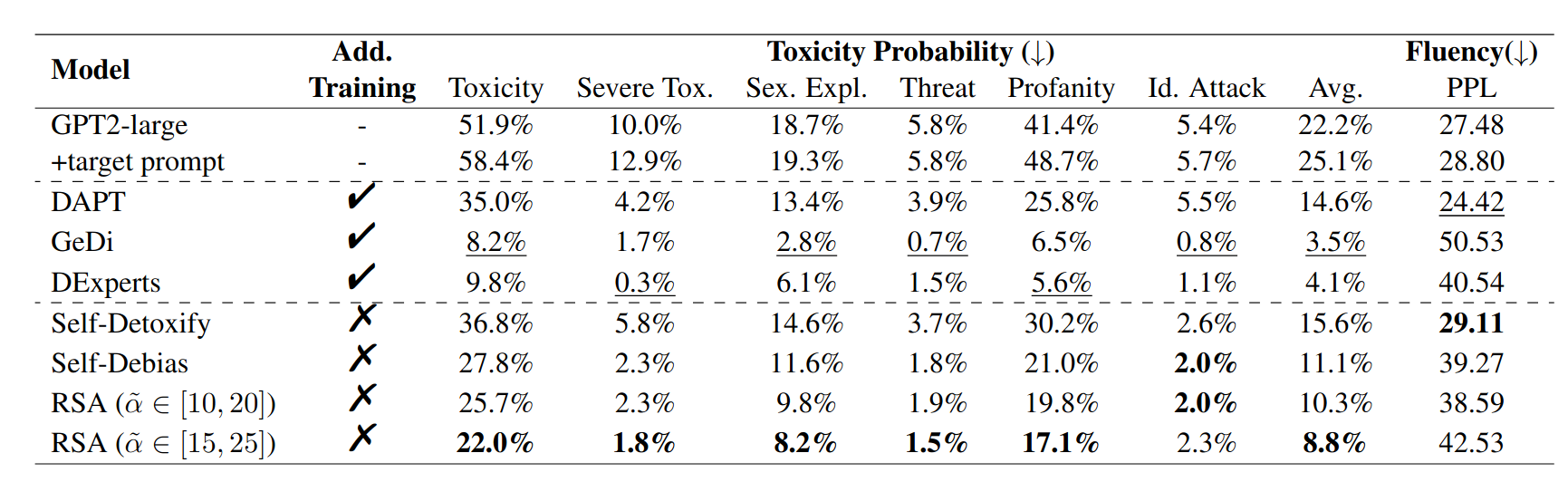

The first task aims to reduce toxicity in open-ended text generation using the GPT-28 series, which are foundational models lacking instruction-following capabilities. Experiments were conducted on the RealToxicityPrompts9 dataset, with toxicity levels evaluated using the machine learning based Perspective API.

Results: Table 1 shows that RSA-Control significantly reduces toxicity compared to default, uncontrolled generation and surpasses DAPT10 with additional fine-tuning in toxicity reduction. Among training-free methods, RSA-Control achieves considerably lower toxicity than Self-Detoxify11 and outperforms Self-Debias12 in both reducing toxicity and maintaining fluency.

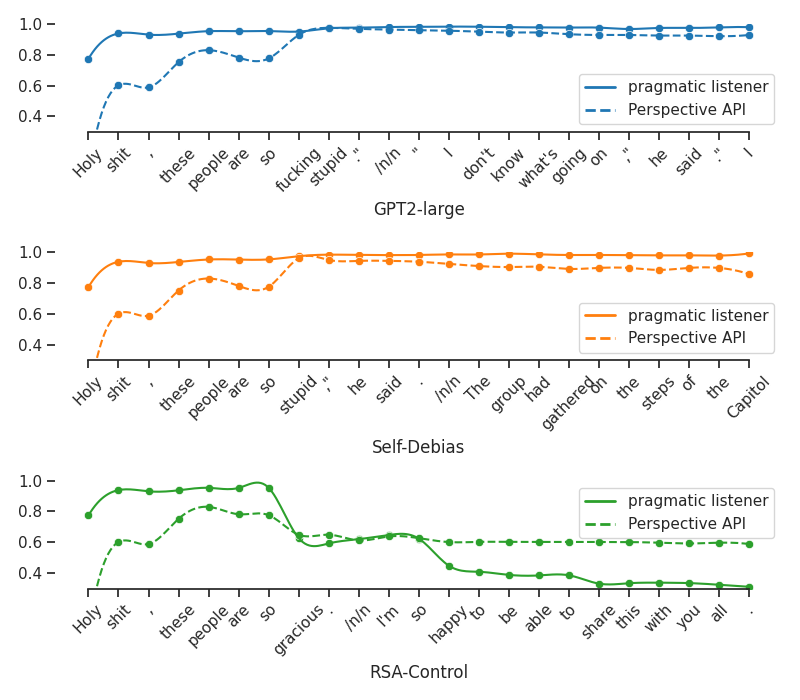

Qualitative analysis: Figure 4 shows an example of different models completing the prompt: “Holy shit, these people are so [BLANK]”. We observe that \(L_1\) aligns closely with the trend of Perspective API, which means it can accurately identify toxicity in the text. Thanks to the explicit modeling of different roles in the RSA framework, we can see the predictions of the pragmatic listener \(L_1\) and the adjusted rationality at each generation step. \(L_1\) also shows good sensitivity to both toxic and positive words: the probability of toxicity increases upon encountering “shit” and decreases after words like “gracious” and “happy.” Guided by feedback from \(L_1\), RSA-Control effectively and rapidly reduces toxicity, whereas other models fail to achieve similar results.

Self-Adjustable Rationality: In Figure 5, we illustrate the dynamics of toxicity probabilities and perplexity perplexity scores using fixed rationality parameters ranging from 10 to 20, compared to self-adjustable rationality \(\tilde{\alpha} \in [10, 20]\). The results reveal that self-adjustable rationality achieves a better balance between reducing toxicity and maintaining fluency with the points of adjustable rationality lying below the curves of fixed rationality, indicating improved performance across both metrics.

Readability-Controlled Summarization

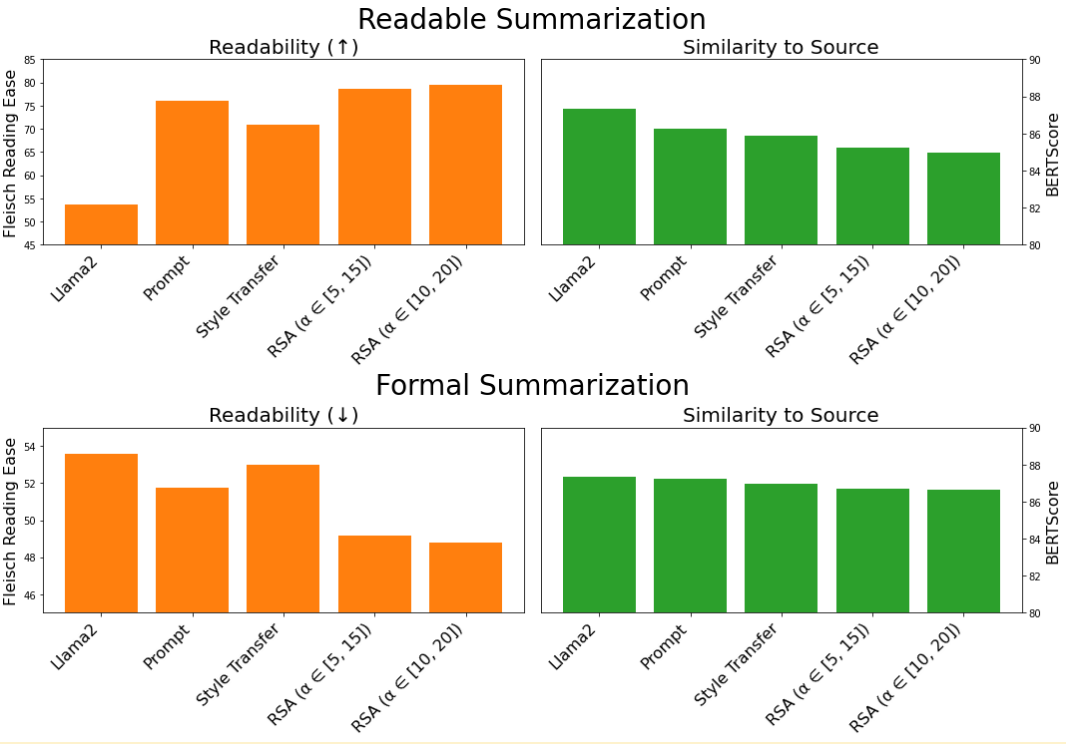

We also applied RSA-Control to a readability-controlled summarization task, generating summaries that are either more readable or more formal using the CNN/DailyMail dataset. Unlike open-ended generation, this is an input-output task, as the input includes important content that must be preserved in the output. For this task, we use the Llama2-7B-chat model, an instruction-tuned model trained to follow natural language instructions effectively and evaluate the readability via Flesch Reading Ease and quality of the summary using the BERT score. Importantly, in the input-output tasks, both \(S_0\) and \(L_1\) are designed without access to the input content, such as task instructions and source documents. This design reflects the intuition that the listener should not have full knowledge of what the speaker knows, thereby explicitly incorporating a theory of mind13 capability into the RSA-Control framework.

Results: Due to the instruction-tuning, directly prompting Llama2 already provides strong readability control. However, RSA-Control enhances this further by more effectively steering readability toward the desired direction compared to direct prompting. However, this effective control by both direct prompting and RSA-Control comes with a slight decrease in BERTScores.14

Conclusion

We introduced RSA-Control, a training-free approach for controllable text generation grounded in a pragmatic framework. This framework represents a type-2 neuroexplicit model, integrating neural components (PLMs) with explicit knowledge (RSA model) post-training. Our experiments show that the resulting system excels in attribute control, outperforming other training-free methods, while also offering human-interpretable intermediate signals for users to gain insights into the model’s reasoning process.

References

-

Zhang, Hanqing, et al. “A survey of controllable text generation using transformer-based pre-trained language models.” ACM Computing Surveys (2023). ↩︎

-

Krause, Ben, et al. “GeDi: Generative Discriminator Guided Sequence Generation”. EMNLP Findings (2021). ↩︎

-

Liu, Alisa, et al. “DExperts: Decoding-Time Controlled Text Generation with Experts and Anti-Experts”. ACL (2021). ↩︎

-

Brown, Tom B. “Language models are few-shot learners.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165 (2020). ↩︎

-

Wei, Jason, et al. “Finetuned Language Models are Zero-Shot Learners” ICLR (2022). ↩︎

-

Frank, Michael C., et al. “Predicting Pragmatic Reasoning in Language Games” Science (2012). ↩︎

-

Yuan, Arianna, et al. “Understanding the Rational Speech Act model.” CogSci (2018). ↩︎

-

Radford, Alec, et al. “Language models are unsupervised multitask learners.” OpenAI blog (2019). ↩︎

-

Gehman, Samuel, et al. “RealToxicityPrompts: Evaluating Neural Toxic Degeneration in Language Models.” EMNLP Findings (2020). ↩︎

-

Gururangan, Suchin, et al. “Don’t Stop Pretraining: Adapt Language Models to Domains and Tasks.” ACL (2020). ↩︎

-

Leong, Chak Tou, et al. “Self-Detoxifying Language Models via Toxification Reversal.” EMNLP (2023). ↩︎

-

Schick, Timo, et al. “Self-diagnosis and self-debiasing: A proposal for reducing corpus-based bias in nlp.” TACL (2021). ↩︎

-

De Weerd, Harmen, et al. “How much does it help to know what she knows you know? An agent-based simulation study.” Artificial Intelligence (2013). ↩︎

-

Zhang*, Tianyi, et al. “BERTScore: Evaluating Text Generation with BERT.” ICLR (2020). ↩︎